For Morris Murenzi, a visit to his native Rwanda always includes attending a gacaca court — a local tribunal of villagers set up to try suspects in a 1994 genocide that killed 800,000.

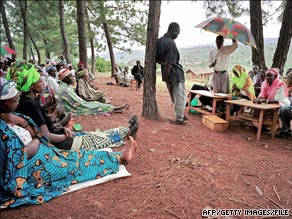

At the proceedings, he sits with his countrymen. Some tearfully confront their attackers and testify against them, their scars from the genocide still visible. Others — like him — quietly listen, their emotional scars invisible. They wait and hope for answers about how their relatives died as a nine-member panel questions suspects. “Some of the witnesses who ask questions are disfigured, others are disabled,” said the Dallas, Texas, resident whose last gacaca trial was in Kigali two years ago. “The attackers have no place to hide. They are forced to address what they have done to the victims.” Murenzi is one of thousands of people who attend gacaca courts all across Rwanda on any given day. Hearings are held in open fields in neighborhoods where the attacks occurred. There are no lawyers and no judges in robes. A panel of local villagers with no legal experience conducts the proceedings. “For me, gacacas help me find closure and healing,” Murenzi said. “I am able to see up close how remorseful the attackers are. … You never see that in real court.”

Don’t Miss

Why Rwanda exploded in violence; what’s happened since

Gacaca courts were introduced in the central African nation after the April 1994 genocide, which raged for 100 days. The victims were mostly from the Tutsi ethnic minority, who were targeted by Hutus over a rivalry that dates to colonial days. Some moderates from the Hutu majority who support Tutsis were also killed. Murenzi, a Tutsi from the capital, Kigali, lost most of his extended family in the genocide. During the attacks, he was in neighboring Uganda with his parents, where he attended school at the time, the 37-year-old said. “My mom’s sisters, brothers, my uncles, they were all killed and buried in mass graves,” he said. The gacacas were originally formed to resolve minor disputes among villagers but were reinvented to hand out justice to the perpetrators of the genocide and help fast-track reconciliation efforts in the broken nation. “You had about 130,000 people in jail. And there were many more outside,” Rwandan President Paul Kagame said recently on CNN’s “Fareed Zakaria GPS.” The nation’s justice system and the International Criminal Tribunal set up to try genocide suspects were overwhelmed, and handling all the cases in those courts would have taken hundreds of years, according to the president. Watch Kagame justify gacacas » “If you went technically to try each one of them, as the law may suggest, then you would lose out on rebuilding a nation, on bringing people back together,” he said. “That’s why we had to say, let’s categorize responsibilities.” The leaders and masterminds of the genocide are tried in ordinary courts, and civilians who contributed to attacks or loss of life directly or indirectly go to gacacas, Kagame said. The tribunals are lacking and fraught with problems, critics say. “We’ve had serious concerns about the gacaca process and whether it meets international fair trial standards,” said Georgette Gagnon, Africa director for Human Rights Watch, which has offices in Rwanda. Some witnesses have been targeted for revenge after testifying, and due process falls short, Gagnon said, adding that the organization has suggested changes to the system to ensure basic human rights are met, but they have not been enforced. “It is time for the process to end. And there needs to be a frank announcement on whether it has led to reconciliation,” she said. Paul Rusesabagina, whose effort to save hundreds of Tutsis was featured in the 2004 movie “Hotel Rwanda,” calls gacacas “the worst idea ever.” “Gacaca traditionally means justice on the grass. Elders sitting on the grass, handing justice to someone who stole a neighbor’s goat,” Rusesabagina said. “Judges are people who never went to school … who do not know anything about law.” Today, this justice is dealing with people who have committed a genocide, which is a much bigger issue, he said. There have been calls to abolish the tribunals, which have tried about 1.5 million cases since they started in 2001, according to the Integrated Regional Information Networks, a U.N. agency. The government in June postponed plans to close gacacas. Some analysts say the system has its advantages, by reducing congestion in prisons and allowing survivors to hear first-hand what happened to their loved ones. Murenzi said he does not have all the answers about his relatives’ deaths, and he plans to attend more gacacas — including during a trip to Rwanda at the end of the year.

Despite the lack of information, he said, watching suspects struggle to come to terms with the attacks has brought an unusual form of comfort. “They will never know peace. They have to live with the fact that they killed their neighbors for the rest of their lives,” Murenzi said. “While the survivors can move on, they (attackers) probably never will.”